Is there really no such thing as free Marketing?

Andreas Bayerl & Maximilian Beichert

Wuhan City, 31st of December 2019: An increasing number of pneumonia cases was reported to the World Health Organization (WHO). Just a week later, Chinese authorities declared that the reason was a new virus and gave it the official name 2019-nCoV. A few weeks later, the city of Wuhan is completely shut down (BBC) and within 6 days the government built a new hospital trying to regain control (CGTN). By now, affected people are reported all over the globe including the USA, France, Germany and Australia.

At the same time, across the globe in Mexico, a beer brand brews around 12,000 liters of Mexican-born lager every day. The brand is around since 1925 and gained popularity by advertising its beer as light and refreshing. This allowed the brand to significantly increase its market share by also reaching peers which were not interested in beer before. Today the Mexico-based brewer is the No. 1 beer importer to the US.

You might ask: What do these two things have in common? It has something to do with the names of the two at first sight unrelated things: The 2019-nCoV virus is clustered into the family of coronaviruses. Thus, the name which now flows through the News 24/7: “The Coronavirus”. The Mexican beer brand on the other side of the globe is named “Corona”. For obvious reasons, the family of coronaviruses has nothing to do with the beer name. The name was motivated through the sun`s corona, which is the name for its outermost part of the atmosphere. The overlapping names motivated us to look at potential spill-over effects from an increase in search terms for the virus to the beer brand.

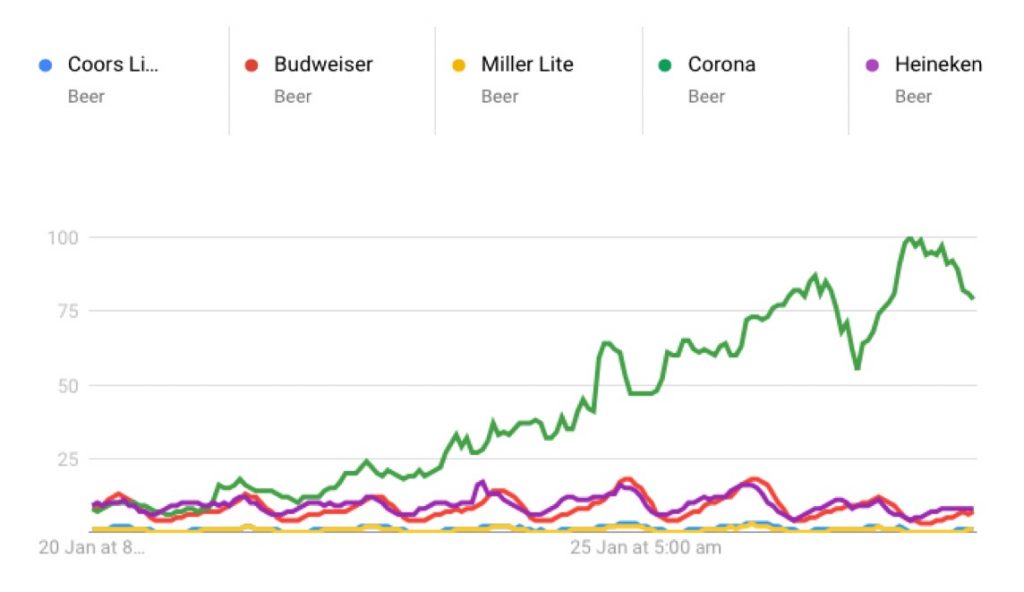

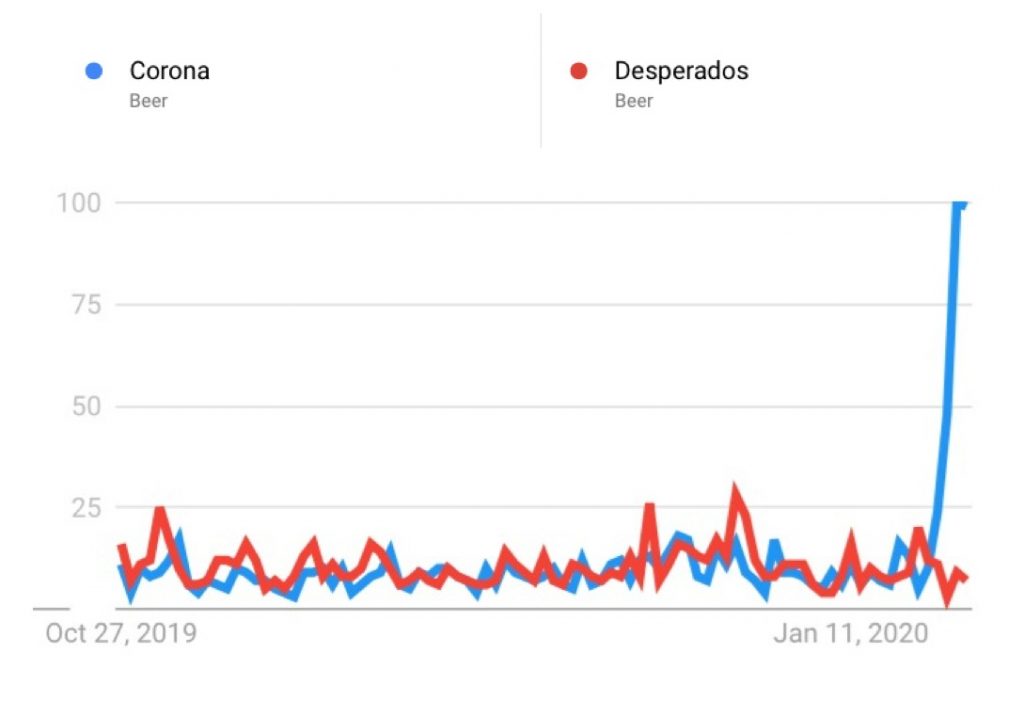

We ran a Google-Trend Analysis comparing worldwide Google Search volume for major beer brands in comparison to Corona beer (see Figure 1). To our surprise we find a strong upward trend for search queries related to Corona beer, while search volume for other American beers stayed at fairly the same level. The same pattern appears once again comparing Google Search volume in Germany for the beer Desperados with the Corona beer (see Figure 2).

Unfortunately, data availability constraints allow us to only analyze search volume until now, but it will be interesting to see whether Corona will also experience an arguably lagged effect in their sales volume. A probable explanation could come from scientific literature around the Mere-Exposure Effect: The Mere Exposure Effect was first mentioned by the psychologist Robert Zajonc (1968) at the University of Michigan. He explained the effect as follows: “The more repeated exposure of an individual to a stimulus is a sufficient condition for the enhancement of his attitude toward it” (Zajonc 1968). The effect describes that the repeated perception of an initially neutrally assessed matter results in its more positive evaluation (Zajonc, Markus and Wilson 1974). For example, familiarity with a product makes that product appear more attractive and likeable. If a consumer is repeatedly exposed to a stimulus, a more positive attitude towards the product, the brand, or the packaging develops (e.g. Baker 1999; Blüher and Pahl 2007; Janiszewski 1993; Olson and Thjømøe 2003). Another positive effect of repeated exposure can be found in brand quality and perceived brand credibility (Kirmani 1997; Scott and White 2016). Increased exposure minimizes the supposed sense of risk when making a purchase and, therefore, the customer feels more secure when making a purchase decision (Baker 1999). The effect increases after multiple repetitions of being exposed to the stimulus (Baker 1999; Janiszewski 1993) and holds even if the stimulus is processed unattentively (Janiszewski 1988). Baker (1999) recognized that the mere exposure effect is particularly important in low-involvement decisions.

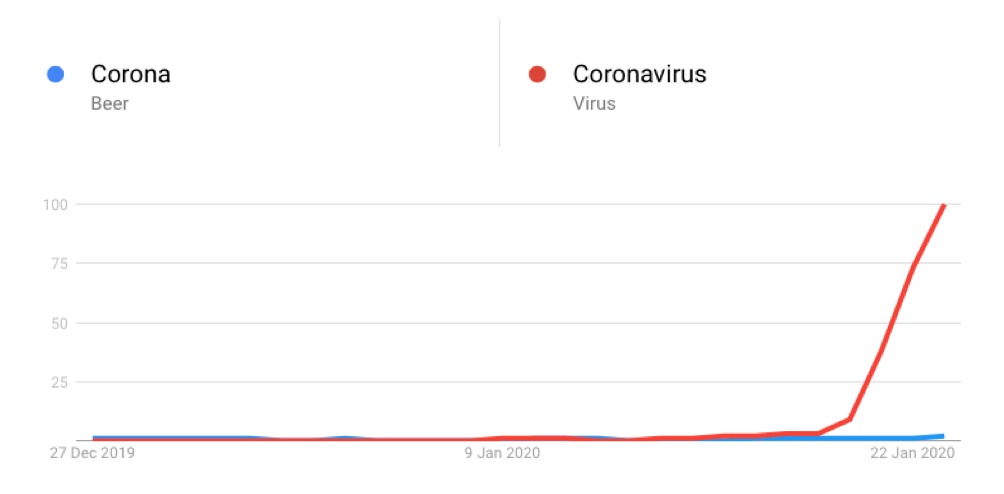

At this point, probably everyone around the world with some access to News will be exposed to the term “Corona” significantly more often. Pechmann and Stewart (1988) reported that the mere exposure effect already appears when the occurrence of a stimulus is between 12 and 15 times within two months (see Figure 3). A number that seems to be easily achieved here in this particular situation. It also doesn’t matter how consciously the stimulus is perceived, because Zajonc, Markus and Wilson (1974) showed that the effect also occurs in subliminal ways. We acknowledge that certainly only a fraction of people that googles “Corona” during these weeks will look for the beer. But still, just the fact that they constantly hear it, talk about it, and search for it arguably has or will have an effect.

The question arises whether these individuals will be more likely to buy the Corona beer when they do grocery shopping the next time. Alternatively, it could also be the other way around: Negative associations with the coronavirus could spill-over to the beer brand and less Corona beer will be consumed. This comes also with evidence from research: The mere-exposure effect does not occur if the assessment was negative at first contact; in this case, repeated presentation makes the dislike even stronger (Zajonc, Markus and Wilson 1974).

Naturally, there are a lot of unobservable variables that are hard to control: E.g., Corona’s advertising strategy together with their competitors’ advertising strategies during the time that we look at. Establishing a sound causal link will require sophisticated statistical tools as described in, e.g., Seiler et al. (2018) or Rossi (2018). A further extension of what we have done could be to analyze the number of increased hashtags over time since the Coronavirus outbreak and company mentions on social media.

Also read the follow-up post “How consumers deal with a product (un)related to a crisis” .

Photo “Outbreak”: (CC) BY SA 4.0 DrFisherCDC, Stefan Kluge; Google-Trends: https://trends.google.com/trends/?geo=US